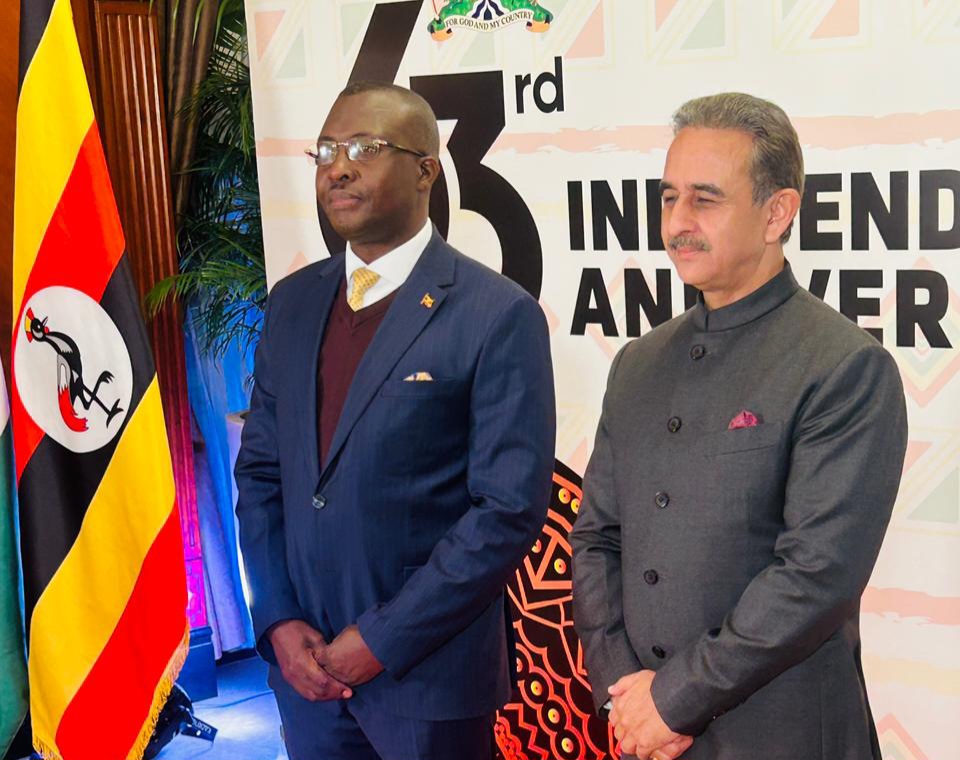

Hon Mulimba John, the Minister of State for Foreign Affairs in charge of regional affairs, recently represented H.E President Museveni at India’s 63rd Independence Day celebrations.

The event was a significant milestone in the strong partnership between India and Uganda, highlighting their shared history of cooperation and mutual growth.

As the guest of honor, Hon Mulimba John delivered a heartfelt speech, praising India’s remarkable progress in various fields and reaffirming Uganda’s commitment to strengthening bilateral ties. He highlighted the country’s shared experiences in the struggle for independence and the importance of continued collaboration in areas like trade, agriculture, and human resource development.

During his visit, Hon Mulimba John also engaged in high-level talks with Indian officials, exploring new avenues for cooperation and ways to enhance economic partnerships between the two nations. He expressed gratitude for India’s support in various development projects and emphasized the need for continued collaboration to address common challenges.

Hon Mulimba John’s participation in the event underscored Uganda’s appreciation for India’s role as a key partner in its development journey. As he prepares to contest for MP Samia Bugwe North Constituency 2026-2031, his diplomatic efforts are expected to further boost the constituency’s growth and development.

The Chief Guest, Shri Kirthi Vardhan Singh, appreciated the strong and mutually beneficial relationship between the two countries. He underscored the role played by Ugandans of Indian Origin and the Indian Diaspora in Uganda who have and continue to contribute towards the development of Uganda. Recalling the warmth and hospitality he experienced at the recently concluded Ministerial Meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement in Kampala on October 2025, Sri Kirthi Singh affirmed that India values its longstanding ties with Uganda and looks forward to deepening this partnership across development, trade and people-to-people links.

Hon. John Mulimba saluted the government and People of India for the continued support towards Uganda’s socioeconomic transformation agenda. The Minister underlined the immense opportunities for future cooperation between Uganda and India across various domains and called for increased investment by India into key sectors of manufacturing, agricultural value addition and special emphasis on tourism and hospitality.

The Minister informed that Uganda’s unmatched tourism products offer unique investment opportunities for Indian companies, as well as exclusive experiences like Mountain Gorilla trekking, chimpanzee trekking, big 5 safaris, mountaineering, white water rafting and religious tourism, among others.